BILL MOYERS:

Welcome. Just before the holidays, we asked you, our viewers, to recommend the one book you thought President Obama should read as he prepares himself for his second term in office. As ever, your suggestions were thoughtful, provocative and eclectic – from books by authors who have appeared as guests on this broadcast, to works by the late John Steinbeck and A. A. Milne, the creator of Winnie-the-Pooh. You can see a list at our website, BillMoyers.com.

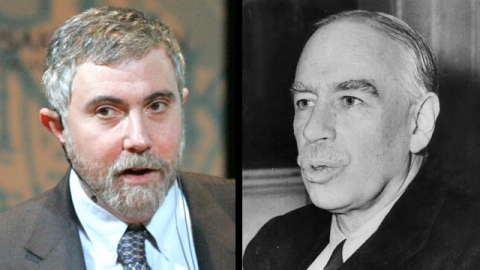

Many of you asked for my choice, too. This is it – Paul Krugman’s End This Depression Now! It’s both prescription and warning: our current obsession with slashing the deficit and avoiding that well-known and worn fiscal cliff is killing us, Krugman writes, getting in the way of what really needs to be done – which is dedicating government to creating jobs and getting us back to full employment. He blames not only Congress but the White House.

Paul Krugman is professor of economics and international affairs at Princeton University. Since 1999, he's been an op-ed columnist at The New York Times and now also writes a blog for the paper titled "The Conscience of a Liberal." According to the search engine Technorati, it’s the most popular blog by an individual on the internet. Author or editor of some twenty books and more than 200 professional papers, Krugman is a thinker so esteemed and widely known in his field he's become an icon. Not only has he won the Nobel Prize in Economics, he’s also the subject of this song by the balladeer Loudon Wainwright III…

LOUDON WAINWRIGHT III:

I read the New York Times that's where I get my news

Paul Krugman's on the op-ed page that's where I get the blues

'Cause Paul always tells it like it is we get it blow by blow…

BILL MOYERS:

As if being immortalized by the blues isn’t enough, there was even an unofficial campaign and petition in the last few days urging President Obama to make Paul Krugman the next Secretary of the Treasury. It was an honor, as Shakespeare would say, that Mr. Krugman dreams not of.

Paul Krugman, welcome.

PAUL KRUGMAN:

Hi there.

BILL MOYERS:

So, like William Tecumseh Sherman you refuse to be drafted.

PAUL KRUGMAN:

Well, you know, fortunately it hasn't come to that point. But I think I probably would.

BILL MOYERS:

But you remember what General Sherman said when there was a movement to run him for president. "I will not accept if nominated and will not serve if elected." That was the Sherman like statement you issued.

PAUL KRUGMAN:

That's, well, I'm not quite up to Sherman's standards and I don't think I'm quite ready to lay waste to Georgia either. But a good, good man I admire actually.

BILL MOYERS:

But the grassroots campaign in your behalf, unofficial, was serious. I mean, over 235,000 people signed on. You broke their hearts. Any regrets?

PAUL KRUGMAN:

No, because I probably have more influence than I, doing what I do now than I would if I were inside trying to, you know, do the court power games that come with any White House, even the best, which I don't think I'd be any good at. So no, this is fine. And what the president needs right now is he needs a hardnosed negotiator. And rumor has it that's what he's got, so.

BILL MOYERS:

In Jack Lew?

PAUL KRUGMAN:

That's right. The president can't pass major new legislation. He can't formulate major new programs right now. What he has to do now is bargain down or ride over these crazy people in the Republican Party. And we what we need now is not deep thinking from the treasury secretary. If the president wants deep thinkers, he can call Joe Stiglitz, he can call other people. What he needs from the Treasury secretary is somebody who's going to be very effective at dealing with these wild men and making sure that nothing terrible happens.

BILL MOYERS:

I understand that Jack Lew has Depression art on his, the wall of his office, art done by the Works Progress Administration. Which would be a good sign for someone like you who believes the Depression is back.

PAUL KRUGMAN:

That's, I have to say, the most reassuring thing I've heard about him. WPA, you know, they produced a lot of art, which I think it's almost inconceivable now. But also the WPA was one of the really good moments in American policy. In a time of economic disaster, hiring people, giving them jobs to do things that are good, much of which survives and is an important part of our physical planet today. This is great. And the fact that he thinks well of and admires what the WPA did, that's a very hopeful sign.

BILL MOYERS:

What could Jack Lew do as Treasury secretary that would make you think he's a kindred spirit?

PAUL KRUGMAN:

Campaign against this austerity obsession. We're not going to get a big new stimulus package, much as I would like to see it. No, we're not going to get it this year, anyway. But I'd like to see him saying when somebody says, "Well, we need to slash here, we need to slash there." And he would say "Why would we want to be doing that now? That's actually going to hurt the economy."

BILL MOYERS:

But hasn't our economy changed so much since Franklin Roosevelt simply put people on the government payroll?

PAUL KRUGMAN:

It's, economics, the underlying rules change a lot more slowly than people imagine. People look and they say, "Oh, you know, back then they were taking ocean liners and now we fly jet airplanes." Or, "Back then we didn't have a global economy." Actually, we did. It's a little bit fancier now. But the basic rules are not are not much changed. It takes hundreds of years for those to change a whole lot. And this is, I can pretty easily assemble a bunch of headlines from the 1930s and they will sound like they're right out of today's headlines. This is the same kind of animal that we confronted in the '30s. This is depression economics. And the nature of the solution is not really very different now from what it was then.

BILL MOYERS:

What do you mean, depression economics?

PAUL KRUGMAN:

Well, two things really. One is, a recession is when the economy's going down. A depression is when the economy is down. So, you know, the U.S. economy was actually expanding through most of the 1930s, after a terrible big slump at the beginning and another slump later in the '30s. And then it was expanding in between. But we call that whole episode the Great Depression because it was all a period of high unemployment and a lot of suffering.

And, of course, we're in that now. It's not as bad as the Great Depression. You know, it's a great recommendation. Not as bad as the Great Depression. It's terrible. We have a persistently depressed economy, persistent lack of jobs. So in that sense, it's a depression. And there's also a more technical meaning. Depression economics is when the normal things you do to boost the economy, have the Federal Reserve cut interest rates a little bit, are no longer available or effective. It's a situation where the normal rules of what you-- of economic policy, have to be put on hold, and you really need to do extraordinary stuff.

BILL MOYERS:

Well, the Fed has kept the interest late very low. And it has made a big difference, has it?

PAUL KRUGMAN:

I think it actually has. If they hadn't kept the interest rate low, things would be much, much worse. Meaning--

BILL MOYERS:

More people out to work.

PAUL KRUGMAN:

That's right. We, you know, this is not as bad as the Great Depression. Again, our famous last words. But part of the reason is that the Fed did learn something from the 1930s. It's learned that raising interest rates to stabilize the price of gold is a really bad idea in times like this. But the trouble is that zero, which is as low as it can get, is not low enough. And we actually know pretty well what you need to do.

BILL MOYERS:

The other side of it is that people have been told so long, "Save money. Save money. Americans were not saving.” Now if they save money, they make no money from their savings.

PAUL KRUGMAN:

That's right. And, actually the truth is right now saving hurts us. It's because what, another way, yet another way to think about depression economics, depression economics is a situation where the total amount that people want to save is less than the amount that businesses are willing to invest. You can think of that as being the result, a lot of it is because of this overhang of personal household debt from the past.

We had a housing bubble that burst, leaving us with too much construction. We have a financial system that's disrupted. But all of that leads to the fact that there's, the amount that businesses are willing to invest is less than the amount that collectively we all want to save, including corporations that are trying to retain earnings.

Which means that we're awash in excess savings. And if you decide to save more, it's not actually going to help society. I mean, things add up. If there's a crucial, one crucial thing to understand about all this it is that the global economy, money moves around in a circle. And my spending is your income, and your spending is my income. And if all of us try to spend less because we want to save more, we don't succeed. All we end up doing is creating a global depression.

BILL MOYERS:

So your prescription in this book, and the book is an argument for the prescription, is that the government should spend more so that people can buy more. In other words, creating demand that will drive the economy. That's the chief argument in here.

PAUL KRUGMAN:

That's right. There are some other things you can do. Debt relief, where you can do it, will help because it will make people able to spend more. There're some things that the, maybe the Federal Reserve can do, even though interest rates are zero. But the core thing, the thing that we know works, the thing that all the evidence of history says works in a situation like this is the private sector won't spend, government can step in and provide the spending that we need in order to keep this economy afloat.

BILL MOYERS:

As you know, there is an argument on the other side that says that Roosevelt, in spending in the '30s, did not really bring us out of the Depression. It was, and you acknowledge this in the book, the war, in which so much money was spent, you couldn't help but put people to work.

PAUL KRUGMAN:

That's right. But the fact that it was a war that finally got the U.S. government to spend enough is not an argument against spending. It's an argument about politics. It's saying that then, as now, lots of people were saying, "Oh, it would be irresponsible to spend," and it wasn't until something external came along that the political restraints were released.

And then, we didn't, we actually were, we had recovered from the Great Depression before Pearl Harbor, because the U.S. economy really went to war in 1940. And presto. I mean, lots of people said, "Oh, spending more can't produce recovery." And then we started our military buildup because war had broken out in Europe. And suddenly, we had recovery.

I made it as a joke, but if we discovered a threat from space aliens and decided that to deal with that threat, we needed to actually, somehow or other we needed to do a lot of infrastructure spending. We needed to build roads and high-speed rail. We would have full employment.

BILL MOYERS:

By full employment, you mean?

PAUL KRUGMAN:

Something like 5 percent unemployment.

BILL MOYERS:

There essentially will always be a certain number of people who are not working for one reason or another.

PAUL KRUGMAN:

Yeah. It's a dynamic economy. There's always going to be companies failing. There's always going to be people quitting a job and taking some time to find a new one. There's a lot of friction in the economy. So the fact of the matter is that normal, a normally pretty full employment economy is still going to have 5 percent measured unemployment. That's okay. But there's a world of difference between that and right now the official number is in the high sevens. But a lot of measures suggest it's a lot worse than that. I mean, and most important, we have four million who've been out of work for more than a year, which is unprecedented since the 1930s.

BILL MOYERS:

Yeah, you write that we are in a depression that is essentially gratuitous. We don't need to be suffering so much pain and destroying so many lives.

PAUL KRUGMAN:

Gratuitous in the sense that there's nothing, the only obstacles to putting people to work, to having those lives restored, to producing hundreds of billions, probably 900 billion a year or so of extra valuable stuff in our economy, is in our minds.

If I could somehow convince the members of Congress and the usual suspects that deficit spending, for the time being, is okay, and that what we really need is a big job creation program. And let's worry about the deficit after we've had a solid recovery, it would all be over. It would be no problem at all, which is what, that's the lesson of 1940, 1941.

BILL MOYERS:

Which is?

PAUL KRUGMAN:

You can find all kinds of people explaining what was fundamentally wrong with the U.S. economy in 1940, that technology makes it impossible, workers don't have the right skill. Then along came a war in Europe and we started spending. Actually, at that point, spending a lot on infrastructure because we were getting ready for a war. And all of a sudden--

BILL MOYERS:

Building harbors, building all kinds of--

PAUL KRUGMAN:

And camps, training camps, there are a lot--

BILL MOYERS:

--training--

PAUL KRUGMAN:

The first thing that happened actually was a lot of construction spending on the giant new camps that the Army was going need. And all of a sudden, all of those unemployable workers turned out to be extremely productive, if you gave them a job. All of those, you know, total inability to get the economy moving turned out to be totally easy to get the economy moving. And we're basically in that situation right now. All the productive capacity is there. All that's lacking is the intellectual clarity and the political will.

BILL MOYERS:

You make this so clear in the book, that's why I recommended that President Obama read this book as the one book I would like to see him read before the inauguration next week. If he read it, what would you hope he would fasten on?

PAUL KRUGMAN:

I would hope that he would fasten on the notion, you know, he faces real political constraint. So we understand, he can't just pass legislation. But that the most important thing, his policy priority right now should be doing whatever he can to at least move in the direction of the kinds of policies that we want for full employment, that we need for full employment. And that the obsessions of Washington about a grand bargain on the deficit are really pretty much beside the point right now. That, if given a choice between doing something that will help the economy in the next two years, and something that will allegedly settle our budget problems for all, you know, for all time, which is wouldn't, that he should go for the stuff that will help the economy now. That he should not bend on that point.

BILL MOYERS:

I can imagine that if you were sitting across the table with him, he might reply, "Look, Krugman, we've got a recovery coming on. Jobs are being created more steadily than ever. Measured unemployment is falling. Households are shaking off their burden of debt. I can see light at the end of the tunnel. I don't think this is the time to do what you're saying."

PAUL KRUGMAN:

I think he might have said that two, three years ago. I don't think that president, you know, we happen to have a very intelligent man as president. He's for real. And he does understand. You can have real discussions with him. And I think he understands that, although things have improved some. We actually have had some progress on the economy in the past year. It's a glacial pace, compared with the way we should be. You can do this various ways. But if you think about the plunge that we took and you look at measures like the labor force, a fraction of prime age workers employed, whatever, we have maybe made up a quarter of the ground we lost in that great plunge in 2008, 2009. And it'll take years and years to get back to anything that looks like prosperity at this rate.

BILL MOYERS:

What makes this a depression? You know, my generation remembers the photographs of those long lines of people looking for jobs, men and women both. Remembers the sad eyes, the hungry stomachs. Remembers that men were becoming so desperate they were becoming militant. But today, even though you say the situation, in terms of joblessness, is like the 1930s, you can't obviously, you can't transparently look around and see the evidence of a depression.

PAUL KRUGMAN:

That's right. It's, and partly that it's not as bad. So by modern concepts the Great Depression had unemployment rates that were as high as 20something percent by modern measures. And even in 1937, when things had improved, before we went into the second leg of the Great Depression, it was still probably about a nine percent unemployment rate by modern standards. And we've got a seven point something, eight percent, whatever. So things are not as bad. But I think a lot of it is just that the optics have changed.

BILL MOYERS:

Optics?

PAUL KRUGMAN:

The optic, the misery is there. I mean, is there anybody, I guess if you live in very rarified circles you don't know people who are desperate right now. But I live in pretty rarified circles and I do. I know, I have relatives, friends people I know who have, men my age who've lost jobs and see no prospect of getting another job and are just desperately trying to hang in there until they can collect their social security and get on Medicare. There are young people whose lives have collapsed. You know, they graduate and there's nothing there.

BILL MOYERS:

Yeah, you make a very powerful point in here of the impact of being out of work now on the lifetime career of a young person who has no job at the moment.

PAUL KRUGMAN:

We have pretty good evidence on, you know, how long does it take to make up for the fact that you happen to graduate from college into a bad labor market. And the answer is forever. You will never recover.

BILL MOYERS:

How so, what do you mean?

PAUL KRUGMAN:

You will never get, you'll miss years getting onto the career ladder. By the time you get a chance to get a job that makes any sense, you know, that makes any use of your skills, you will already be tarred as somebody, "Well, you're 28 years old and you haven't held a responsible position?" "Well, yeah, I couldn't because there were no jobs." It just shadows your whole life. And it's very clear in the evidence from past recessions, which have been nowhere near as bad as this one.

The other thing I think I want to say here is that we have, in some ways, made things more civilized but also more invisible. Somebody said that food stamps are the soup kitchens of the modern depression. That there're a lot of people who would be standing in line to get that soup, who are instead, and it's a good thing, who are instead getting, I guess it's now called SNAP, Supplementary Nutritional Assistance Program, but who are getting those debit cards, and are getting essential food stuffs. And they're at the grocery store and they look like anybody else. But the fact of the matter is they are still as desperate, they're getting by day to day with the aid of a trickle of government aid, just like the people who were on, standing in line at the soup kitchens in the '30s, but they're not visible. They, we don't have guys selling apples in street corners partly because, you know, the city licensing wouldn't allow that anymore.

But we do have, again, we've got four million people who've been out of work for more than a year. The U.S. social system is not designed to take care of somebody who's been out of work. We have unemployment insurance that's intended to deal with short spells of unemployment. So there's an enormous amount of misery, but it is mostly hidden.

BILL MOYERS:

So that's why you refer to it, even though the optics have changed, as a quote "Vast, unnecessary catastrophe"?

PAUL KRUGMAN:

Yeah. The amount of damage that's being done is enormous. The amount of suffering of people is enormous. And if it isn't out there, visible on the streets, if it's dispersed across a suburban you know, if you see a house with a for sale sign that's been sitting there for a while, you may not know the story about the family that was driven from its house because they, one or both spouses lost jobs and couldn't find others. Or, and they were foreclosed on. But it's a real story, all the same. And there's lots of that going around. And none of this needs to be happening.

BILL MOYERS:

And you argue that this could actually be solved in two years?

PAUL KRUGMAN:

That's right. And that's not a number plucked out of thin air. That's a guess at how long it would take to get a serious spending program going. And we could actually make a lot of difference in it even quicker than that because the fact of the matter is, far from having effective job creation program, we've actually been pulling back. We've seen state and local governments lay off hundreds of thousands of school teachers. We've seen public investment in basic stuff like road repair cut way back. If we just went back to normal rates of filling potholes and normal rates of employment of school teachers, that could be done in months.

BILL MOYERS:

You wonder why, given the suffering, Congress and the White House haven't acted.

PAUL KRUGMAN:

Well, there are I think two, two levels of opposition. And one of them is just raw politics. We have a powerful political movement in this country that has a longstanding goal of rolling back all of the social programs, all the safety net that we've created. They want smaller government. They want reduced public services. Even the idea of public schools is very much under attack. They want it all to be switched to a system of vouchers. And they see this, you and I see a disaster, they see an opportunity. Here we have cash strapped state and local government. Good. Forced to cut back in government. They don't want to do anything that will make it easier for them to, for government as we know it to continue. That movement controls one political party. And that political party controls one house of Congress. And that is enough to stand in the way of a lot of things we ought to be doing. Then there's the second level, which is this odd coalescence of, I picked up the phrase from other people. Actually, from the blogger Duncan Black. "Very Serious People," capital V, capital S, capital P.

BILL MOYERS:

You're always writing that these Very Serious People. Who are they?

PAUL KRUGMAN:

Yeah. The notion that someone, well, you can look are your random set of, you know Erskine Bowles and Alan Simpson would be the quintessential Very Serious People. The editorial, practically the whole op-ed page, not all of them, but most of "The Washington Post." People for whom this, it's axiomatic that the budget deficit is the most important problem. And that what we really, really need to do right now at a time of mass unemployment is worry about the debt to GDP ratio ten years from now. And it's a very hard thing to crack, partly because it's not actually a rational argument. You very rarely, very rarely see on the Sunday talk shows, people asking, "Why exactly are you so concerned about the deficit right now?" That's sort of a given. That's a starting point. Everybody serious understands that, except that if you ask them why exactly, they can't give you a very good answer.

BILL MOYERS:

What is the answer?

PAUL KRUGMAN:

It's partly that this is, it sounds serious. Never you know, never underestimate the importance of just plain what comes across. Start so it's partly just it sounds serious, it's the kind of thing that people who wear good suits are likely to talk about. Partly it is actually, of course, a deliberate pressure campaign.

BILL MOYERS:

For example, Pete Peterson, Nixon's Secretary of the Commerce, billionaire several times over has set up this Fix the Debt campaign and is said to be putting half a billion dollars into trying to influence the public.

PAUL KRUGMAN:

Yeah, actually it's not just Fix the Debt, that's just the latest incarnation. There's also the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, there's the newspaper "The Fiscal Times," there's several others. It's a whole portfolio. They all are Peterson Foundation money at the roots, but they're all out there. And yeah, serious attempts to influence public debate are not, by and large, a very lavishly funded enterprise.

BILL MOYERS:

But in this case?

PAUL KRUGMAN:

But in this case, you've got so half a billion dollars, $500 million of spending with one agenda is going to have a huge impact. You know, policy intellectuals, by and large come cheap. A few hundred thousand in consulting contracts could do a lot there.

BILL MOYERS:

Do you think some of them are serious about the debt leading to a loss of confidence on the part of investors in foreign governments? I mean, even three years ago Barack Obama expressed concern about the long term debt and the confidence of people in the U.S. government. Take a listen.

BARACK OBAMA:

There may be some tax provisions that can encourage businesses to hire sooner rather than sitting on the sidelines. So we're taking a look at those. I think it is important, though, to recognize that if we keep on adding to the debt, even in the midst of this recovery, that at some point, people could lose confidence in the US economy in a way that could actually lead to a double-dip recession.

PAUL KRUGMAN:

I remember that well. And at the time it was going on, I do occasionally find myself in meetings with Very Serious People myself. I guess I am personally one now and then. There was this widespread view among people, and not all of it venal, not all of it self-interested, that somehow things were hanging by a thread. That any day now we could have a run on U.S. government debt, which was wrong.

But, okay, I can see how people could for a while have believed that. But a lot of time has gone by since then. And I hope that at least some people have learned better. But it's amazing how little the continued failure of these warnings to actually be vindicated by anything has…how little of that's actually affected the debate.

And there's a special issue here, which I've actually tried to get across now, and I find that I get resistance even from people who are, I would've hoped were more flexible. It's even very hard to tell the story about how this loss of confidence is supposed to work. I mean, it's the United States is not like a European country that doesn't have its own currency.

The U.S. government cannot run out of cash unless Congress prevents it, you know creates an entirely self-inflicted shortage through the debt ceiling. How is it exactly that we're supposed to have this crisis that leads to a double dip recession? It really doesn't even make sense as a story. And yet it is one of those things that people say and by and large, are not contradicted on.

BILL MOYERS:

We keep hearing from the right that we're here on the path to becoming Greece, and you say that that's impossible?

PAUL KRUGMAN:

Yeah. We, even if, suppose that people decided, investors decided they don't like U.S. government debt, it can't cause a funding crisis because the U.S. government prints money. It’s even hard to see how it can drive up interest rates because the Fed sets interest rates at the short end, and why exactly would the long run rates go up if you don't expect the Fed to raise rates? It could lead to a weakening of the U.S. dollar against other currencies.

But that's actually a good thing. That would make U.S. exports more competitive. That would actually boost our economy. So it's, actually impossible to tell that story, as far as I can tell. And yet, it's not, again we're mostly not in the realm of rational discourse here. It's one of those things where people say it, they hear other people saying it. And they don't actually try to work it through.

And it plays a big role, I'm sorry, in influencing our public discussion. Interestingly, people who actually have money on the line, that is people who are buying bonds, just keep on driving U.S. interest rates ever lower. So actual investors don't care about this stuff. But our political class does.

BILL MOYERS:

Why don't they care?

PAUL KRUGMAN:

Because first of all, because I think at some level investors understand what I'm saying. That it's very difficult to see any reason why the Fed would raise short term rates, which is controls for years to come. And in that case, long term debt even at a pretty low interest rate is a reasonable investment. Hard to see how a financial crisis actually develops against the United States, U.S. government, which is in this you know, has all the luxury of printing its own currency.

And investments are always about compared to what, right? If you if you say, "Well, the U.S. is a dangerous place to invest," I don't think it is, but particularly where is the safe place that people are going to invest? You know, what is this other asset that they're going to buy? And it doesn't really exist.

BILL MOYERS:

You say we're in a liquidity trap. I don't understand that.

PAUL KRUGMAN:

Basically, a liquidity trap is we're, back up for a second. How do we normally deal with a recession? How do we deal with a garden variety recession like the 2001 after the dot com bubble burst, or 1991? The answer is that basically the Fed, the Federal Reserve goes out there and prints money.

Or strictly speaking credits banks, you know, credit banks with that extra reserves and buys treasury bills. And that normally starts a chain of events where, okay, the banks have got extra reserves, they lend them out. They, that drives down interest rates, leads to a whole series of events, which ends up with the economy picking up some steam. And what the Fed is doing in that case, it's supplying extra liquidity to the system.

PAUL KRUGMAN:

But now we're in a situation, we're awash in liquidity. We've already got, I mean, interest rates are zero. And so anybody you say, "Well, we're going to give you some more cash and you're going to go lend it out," and banks, everybody's going to say, "Well, why would I want to do that? I mean, interest rates are zero. It's, there's no particular incentive for me not to just sit on this cash."

So you pour this extra liquidity into the economy and it just sits there. And that's the liquidity trap. It's a situation in which the ordinary monetary policy thing doesn't work.

A side consequence of that is it also means that if the government goes out and borrows more, it's not going to drive up interest rates because there's all this cash sitting out there looking for a place to go.

So the rules change. And liquidity traps are really rare. I mean, we had one in the 1930s and we've had another one since 2008. And aside from that, we had one in Japan in the 1990s, and that's about it. But when they happen, boy, they change all the rules. You find yourself in a different universe for economics.

BILL MOYERS:

And they're not putting people to work.

PAUL KRUGMAN:

That's right. A liquidity trap is a situation where the economy can stay depressed and there's no natural, certainly no fast natural route to recovery.

BILL MOYERS:

So why would you be calling for more spending, given that reality?

PAUL KRUGMAN:

Oh, but that’s the point, then the equation, what we’re looking for always, the problem…Basically all recessions are a problem of not enough spending in the economy. There are a few exceptions, basically, what we call a recession is, a case where there's not enough spending, and so there's not enough jobs. Normally, however, you can deal with that in a very narrow technocratic fashion, which is that the Federal Reserve cuts interest rates and stuff happens.

Now that doesn't work because we're in a liquidity trap. And so, this is where you say, "Okay, we need something else that's going to work, and it's very hard to come up with anything that is clearly effective, other than having the government go out and spend the money that the private sector won't." And this is why it, you know, this is, monetary policy is the aspirin of economic ailments. Take a couple whenever you're feeling that you have a headache. Now we had the over the counter remedy doesn't work and we need the, the heavy duty prescription medicine, and that's what I'm arguing for.

BILL MOYERS:

Interesting you say that because I tried to condense to one sentence the message and argument of your book. And I wrote down, "The answer is simple. Increase spending and boost consumption because the fundamental problem at the root of this crisis is a lack of demand."

PAUL KRUGMAN:

That's it. Now you can say that all crises’, or most crises’ anyway, most recessions are a lack of demand. But this is an intractable lack of demand. And so, we, we need we need government action of a type that most, at any point during the past 70 years, except this one, I would have said, "No, let's leave it up to my former colleague, Ben Bernanke." But he can't do the job right now. And so, we need the government.

BILL MOYERS:

And if the president were sitting across the table from you and asking, "Where would you spend this money, Paul?" What would your answer be?

PAUL KRUGMAN:

Right now it's easy because right now we can do it very quickly simply by restoring the spending cuts that have already happened. If you gave me unlimited carte blanche in terms of spending, I would want to go beyond that. I'd want to talk about and pretty straightforward things, even so. We have you know, fix the sewer lines. I mean, we have, we have a lot of, a lot of basic infrastructure needs that are worth doing in any case.

But right now you can get a quick boost just by rehiring those school teachers and filling those potholes. We are something like $300 billion a year short of the spending that we should be undertaking just for the normal business of government. And that extra $300 billion a year would be a really big deal for the economy if we could do it right now.

BILL MOYERS:

Would it bring us to what you call full employment?

PAUL KRUGMAN:

Probably not. Probably bring us down to an unemployment rate that was more in the 6 to 6.5 percent.

BILL MOYERS:

How much would it add to the long term deficit?

PAUL KRUGMAN:

Actually, nothing to the long term deficit, or almost nothing because this would not be a permanent set of measures. This would be something we'd do now. It would add headline suppose we spend $300 billion a year right now, additional. That's not $300 billion a year in extra debt because it's, the economy will be stronger, which means more revenue, which means less spending on unemployment benefits.

So it's probably under $200 billion a year in immediate borrowing. And there's a lot of reason to think that would actually, having a stronger economy now would actually strengthen the economy in the long run as well. Or put it this way, the other way, that having a really weak economy now is damaging our future and not just our present. Think about all college graduates who will never get the job they all should get.

That's not just harm for them, that's a future economy that is weaker than it should've been because it's wasting a lot of our talent. And there's a pretty good case, actually a pretty strong case, that if you think about the long run fiscal impact, spending more right now is actually positive even in terms of the long run budget situation because a stronger future economy will mean stronger revenue down the pike.

And the debt we incur right now, well, you know, the interest rate on U.S. long term debt is under 2 percent. Inflation protected U.S. long term debt has a negative interest rate. There's almost no, there's even, on purely fiscal terms, it's arguable that we should be spending more just to strengthen our long run budget position.

BILL MOYERS:

Is there a limit to how much we can keep borrowing?

PAUL KRUGMAN:

There may be, although all that we know, all of the evidence says it's a lot further away than conventional wisdom has it. I mean, like a lot of people, including Ben Bernanke, I got into all of these things by looking at Japan in the '90s. And Japan famously has run deficits year after year. And it has a level of debt that is about twice what we've got as a share of GDP.

And people have been predicting financial catastrophe for Japan year after year for ten years or more. They've had downgrades. Their debt was downgraded in 2002 by the major rating agencies. And everybody who believed those warnings and everybody -- has lost a lot of money. So it turns out that if you're an advanced country with its own currency and a reasonably stable government, you have a lot of running room on these things.

So am I worried? Yeah, I mean, I am worried about the U.S. fiscal situation 20 years from now. We do have a problem of health care costs and so on. But, you know, I'm worried about a lot of other things 20 years as well. I'm not sure that even if you take that long term perspective, that the budget should be at the top of your list of things to be afraid of.

I'm a lot more afraid, actually, of the great -- the entire southwest of the United States turning into a dustbowl because of climate change, right? So sure, by all means, let's think about it. But it should not be dominating our policy discussion now.

BILL MOYERS:

As you know, we're heading toward another knockdown, drag out, shoot it out at the O.K. Corral fight over raising the debt ceiling in a few weeks. President Obama has already said he will not negotiate on raising the debt ceiling. Here's what he said.

BARACK OBAMA:

I will not have another debate with this Congress over whether or not they should pay the bills that they’ve already racked up through the laws that they passed. Let me repeat. We can’t not pay bills that we’ve already incurred.

BILL MOYERS:

And here's the response he got the next day from Republican Senator Pat Toomey of Pennsylvania.

PAT TOOMEY:

Our opportunity here is on the debt ceiling. The president's made it very clear; he doesn't even want to have a discussion about it, because he knows this is where we have leverage. We Republicans need to be willing to tolerate a temporary partial government shutdown, which is what that could mean, and insist that we get off the road to Greece, because that's the road we're on right now. We only can solve this problem by getting spending under control and restructuring the entitlement programs. There is no tax solution to this; it's a spending solution. And if this president doesn't want to go there, we're going to have to force it and we're going to have to force it over the debt ceiling.

PAUL KRUGMAN:

This is a guy walking into a crowded room and saying, "I have a bomb strapped to my chest, and if you don't give me what I want, I'm going to blow up everybody, including myself." And is that a credible threat? Well, there're some pretty crazy people there. And it might be that they're willing to do it.

But by the same token, Obama cannot get into this because then you have government in the hands of -- never mind the Constitution, the government is run by whoever is most willing to wreak havoc with our whole system of -- with the nation. We cannot allow ourselves to be blackmailed into spending cuts, partly because blackmail should not be part of how the U.S. operates, and partly because spending cuts would be disastrous right now. So Obama's right to say he doesn't negotiate. I'd like to know exactly what he will do if it turns out that there is not a quorum of sane people in the Republican party.

BILL MOYERS:

If you were Secretary of the Treasury, what would you recommend he do?

PAUL KRUGMAN:

I'm for whatever gimmick works. So the most dignified is to say, "Look, this is ridiculous. You are giving the president -- effectively Congress is giving the president inconsistent instructions. It's passed bills mandating spending. It's passed bills that give us inadequate revenue to cover that spending which requires that we borrow. And then you're saying, 'I can't borrow.' Well, you know.

And my reading of the Constitution is I have to obey the due legislative process and go ahead and do this borrowing to meet the bills that we've already incurred, as the president said." That's sort of what people are calling the Fourteenth Amendment solution, that basically it's unconstitutional to give into this debt limit thing. I guess that's your best solution. They don't think that that's workable then you go for anything at hand. And there is this wonderful bit about the platinum coin.

BILL MOYERS:

I don’t understand that.

PAUL KRUGMAN:

In a 1997 act amended in 2000 which covers issuance of coins and stuff like that. There's one clause that says that the Secretary of the Treasury shall have the right to mint and issue platinum coins in any denomination that he so chooses. Clearly, the intent was commemorative coins. You're going to strike a coin to commemorate whatever, Mother's Day.

But it doesn’t say that. And as far as legal scholars have been able to make out, there's no reason why the Secretary of the Treasury can't order the minting of a coin that says this coin is worth $1 trillion, which need bear no relationship to the actual value of the platinum in it. It has to be platinum, however. And walk that coin over to the Federal Reserve.

Deposit it in and have the Federal Reserve create a bank account for the federal government based on that coin of whatever. It could be one coin for $1 trillion, it could be a thousand coins of a billion each, whatever. And then the government can pay its bills by drawing on that bank account. And it's crazy, it's an accounting gimmick, but then this whole thing is crazy. And if that lets you bypass this nonsense about the debt limit, fine.

There are other routes. I mean, it's possible the government could issue coupons that look like debt and function like debt, but says, "No, they're not debt." They could say, "This -- we have no legal obligation to pay this. We are, in fact, going to pay it, but we have no legal obligation to pay it." That's another alternative. They could--

BILL MOYERS:

This is what you'd call--

PAUL KRUGMAN:

I'd call it moral obligation coupons.

BILL MOYERS:

Moral obligation because the government is morally obligated to pay that at some point, right? That’s what--

PAUL KRUGMAN:

That's right.

BILL MOYERS:

--you mean by that?

PAUL KRUGMAN:

Yeah. So, but it's a moral obligation. We can say it's not a legal obligation so that -- you know, all of this is of course, this is all word games. But then that's not to play games would be irresponsible at this point.

BILL MOYERS:

So you would encourage, if you were Secretary of the Treasury, the president to call the Republican bluff?

PAUL KRUGMAN:

Yes. I think, now, I think you probably don't commit to doing that until we actually hit the limit. You say what the president is now saying. There is no alternative but for Congress to do the responsible thing and raise this debt limit.

But you don't rule out these alternatives and you make sure that the Republicans know you haven't ruled it out so that it stands ready, and in fact it’s what you do. Hostage negotiations, you have to -- you have to have some credible alternative to giving into the hostage takers demands, and that's where we are right now.

BILL MOYERS:

You've confessed before to an occasional sinking feeling that you can count on President Obama to wimp out. And that's your term, "to wimp out" when it matters.

PAUL KRUGMAN:

Yeah. The 2011 debt ceiling fight was deeply disheartening because he should not have negotiated on the debt ceiling at all. Same argument as now. This is not how you do it. It is not a legitimate tactic of politics to threaten to destroy the country if you don't get what you want. And people who make that demand have no standing. You should not give them anything.

But he did. He actually did, in fact, make some significant concessions on spending, in order to get a rise in the debt limit. He blinked a little bit on the fiscal cliff. Not as badly as some of us feared, but he did not, in fact, hold out for the full revenue package. And so, some of us are worried. Now, I have to say, I mean, I'm reading my own stage directions here.

People like me are, in part, going after him, warning about the wimping out thing in order to turn that into a self-denying prophesy. That the idea is to make a situation where the president will be aware what people will say about him if he does give in here so it doesn't happen.

BILL MOYERS:

More than many economists I read, you keep politics at center stage in writing about the economy. Those are two different narratives in one sense. And yet, you intertwine them as you keep writing and analyzing our situation today. Why is that?

PAUL KRUGMAN:

I think we've reached a moment in our history where the extreme nature of our politics and the extreme nature of the economic situation has converged. You know, here we are, on one side we have a once-in-three-generations economic crisis. Right, this is -- starting in 2008, we've been experiencing the crisis that has haunted the nightmares of macro economists since the 1930s. And here it is again.

And this is as dramatic as it gets. It's a situation where you really have to throw out the business as usual. And on the other side, you have this extreme political situation, where a radical movement has taken over one of our two great political parties. And does not-- does not practice politics as usual. Anyone who talks about, "Well, we should make deals the way we used to. What about the Tax Reform of 1986? Why can't we do that again?" And the answer is, well, that might make sense to you if you've been in a Buddhist monastery for the past 20 years.

But that's not today's Republican party. You can't make that kind of deal with them. And so, how can you write about the economics? If you write about economics right now and implicitly adopt the perspective, "Well, let's get reasonable people together in Washington and reach a solution here," you know, you're paying no attention to reality. And, of course, if you talk about the politics without talking about the economics, you're also missing everything. So how could I not be writing about both?

BILL MOYERS:

You begin one chapter of your book with a quote from your intellectual mentor, John Maynard Keynes, who writes in his masterpiece The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, "The outstanding faults of the economic society in which we live--" and this was the ‘20s and '30s, "are its failure to provide for full employment. And its arbitrary and inequitable distribution of wealth and incomes." Well, we don't have full employment today and we have gross inequality in income. So which is failing us, capitalism or democracy or both?

PAUL KRUGMAN:

I guess I have a -- here's where I guess I am an optimist, which is that I believe that you can fix both capitalism and democracy. Not to produce a utopia, but to produce a workable solution. And the reason I believe that is we did that for a pretty long stretch.

Western economies in 1933 and western societies in 1933 were in a pretty horrible state. Mass unemployment, gross inequality, collapse of democracy in a number of places. And in the end, by the time 1950 had rolled around, we had managed to create a more equitable, not totally equal, but a more equitable society, with reasonably full employment.

And that solution lasted for half a century, which is all you can ever expect in human affairs. Nothing is permanent. So I do believe that we can do that again. So it's not that we have to ditch capitalism. I think a market economy is -- this is probably Churchill, right, it's the worst solution except for all the others. And democracy is the worst system, except for all the others.

But it's going to take some work. It's not -- the idea that you can just let markets rip and that you don't need to worry about the state of your democracy, that's wrong. But I'm actually, in a way, a conservative on these things. But a conservative, not -- what we now call conservatives are actually radicals who want to tear down the structure that we built, starting with FDR. And I want to rebuild something like that, a modernized, a twenty-first century version of that system. But it's not out of reach. It's not something that can't be done.

BILL MOYERS:

Paul Krugman, “End This Depression Now.” Thank you very much for this conversation.

PAUL KRUGMAN:

Thank you.

Krugman on Keynes

Krugman on Keynes